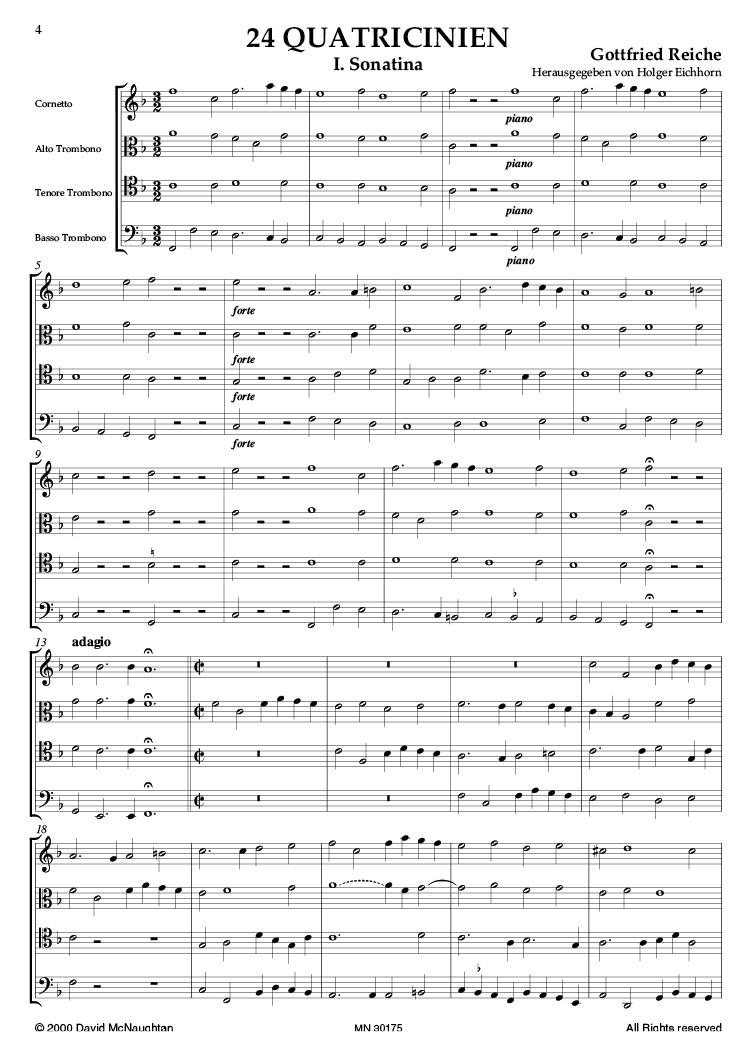

Reiche 24 Quatricinia

Instrumentation: Cornetto, 3 TrombonesDifficulty (I-VI): IV-V

Parts for: Part I: Cornetto, Trumpet in C

Part II: Alto Trombone, Trumpet in C

Part III: Tenor Trombone, Horn in F

Part IV: Bass Trombone

Series: Edward Tarr Brass

Editor: Holger Eichhorn

Gottfried Reiche, whose "Vierundzwanzig Neue Quatricinia" (Twenty-four New Quatricina) are presented here for the first time in an "Urtext Edition", is for several reasons to be considered as one of the most important personalities in German musical life around 1700. We know no more about his life than can be read in older sources – he was born in Weissenfels, a town with a considerable tradition of brass playing, and moved to Leipzig in 1688 as a trainee "Stadtpfeifer". In 1700 he achieved the title of "Kunstgeiger" – literally translated the term means a violin virtuoso, but in this case it is the title of a town musician of low social rank –, in 1706 that of "Stadtpfeifer" and became their director in 1719. Reiche. who made an extraordinary contribution to the musical life of his adopted home town of Leipzig, died there in 1734 – allegedly because of the strain of playing the first trumpet part of “Preise dein Glücke, gesegnetes Sachsen” (BWV 215). The fact that Reiche, at 67 years of age, was still capable of playing such demanding parts demonstrates his extraordinary capability – in the later version of the same piece, the Hosanna of the Mass in b minor, Bach reduced his demands on the player considerably. Reiche's rare ability as a trumpet player – for example his capacity for “bending” the natural tones or his exceptional range – ensures him an important place in musicological history as the inspiration for the exceptionally interesting and difficult trumpet parts in Bach's cantatas and oratorios.

It was expected of the director of the “Stadtpfeifer” – at that time the highest office a town musician could achieve – that he should also be able to play a variety of other wind instruments: the slide trumpet (the historical predecessor of the trombone, which was first invented in the 15th century), horn and cornetto (e.g. in at least 12 of Bach's cantatas). He was of course also expected to play the trombone, for instance in BWV 2, 21, 38 ... ; – alto trombone at times in the very top register (up to a"). Reiche experienced the final flowering of the trombone as an important, sometimes virtuoso solo instrument before it was degraded to being an harmonic member of the grand orchestras and wind bands of the 19th centrury.

Instrumentation and Reiche's “Quatricinia”

In addition to Bach, almost all composers of the 17th and early 18th centuries wrote occasionally for cornetti and trombones. Thus – albeit exclusively – also Gottfried Reiche, whose official duties included the daily “sogenannte Abblasen auff den Rathhäusern oder Thürmen mit Fleiß gestellet” (so-called fanfare from the town halls or towers diligently played). To this end he published – allegedly following 40 sonatas for 2 cornetti and 3 trombones, dedicated to the Leipzig town council and now lost – the “Vier und zwantzig Neue Quatricina...” in 1696.

This long lost and lamented collection, now happily rediscovered and with this edition presented in ist original form, can be regarded as an important milestone in the history of wind chamber music around 1700, even though Reiche and his time would have used the music for other purposes than chamber music.

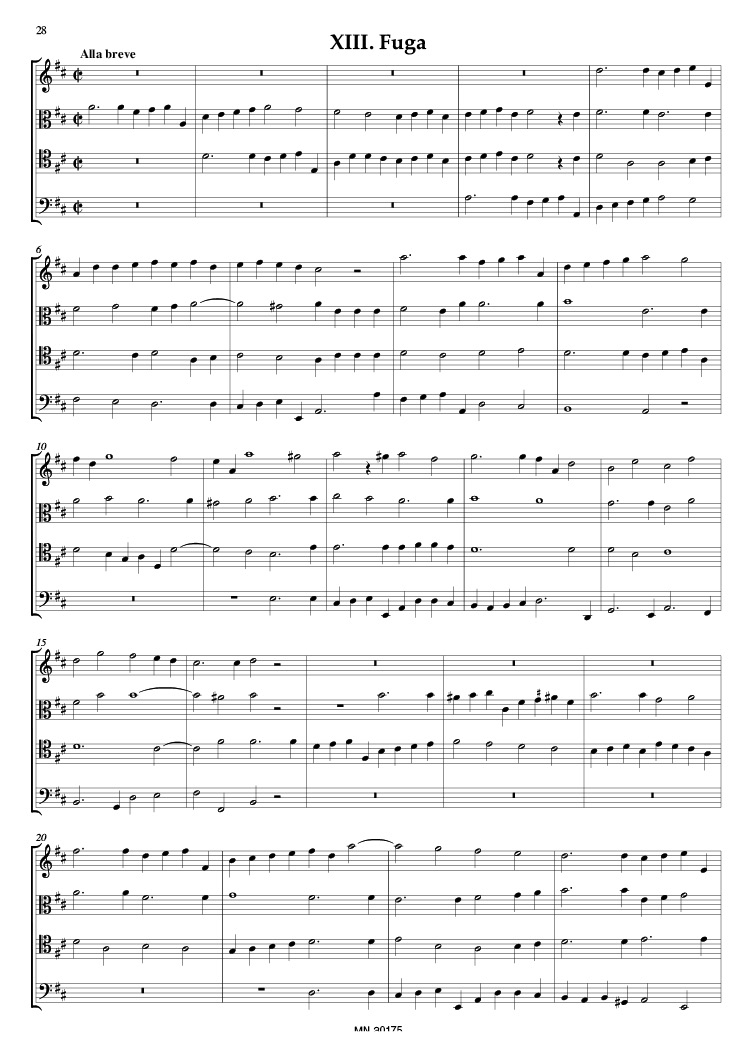

Following Matthew Locke’s Coronation Music “ffor His Majesty’s Sagbutts and Cornetts” (London 1661, published for the first time with all seven movements by mcnaughtan as “Five-Part Things for the Cornetts”, edited by Edward H. Tarr), the “Hora Decima” (1670) and “Fünff-stimmige blasende Musik” (1685) of his predecessor in office Johann Pezel, the contemporary pieces (1685) by Daniel Speer and the six Sonatas of J. G. Chr. Störl, Reiche’s Qautricinien can be seen as works of the first rank, both because of their variety and because of their refinement. In general, within the context of their time and the contemporary musical situation, Reiche’s Sonatinas and Fugues present themselves as a fortunate rarity, especially as the time for such ensemble music was (in theory) long gone. Although the repertoire of the “Stadtpfeifer” for their daily Tower Music contained more than just chorales, dances and fanfares, almost all contemporary composers of the late 17th and early 18th century wrote only for strings and the more “modern” wind instruments (flute, oboe and bassoon) instead of for the traditional Stadtpfeifer instrumentation, which even Bach considered to be the “stile antico” (cf. Bach’s cantata movements and his arrangement of Palestrina’s “Missa sine nomine”). Reiche’s works therefore take up an important place in musical history, because they are both unique and innovative, less though because of the quality of their composition. It is important, however, to bear in mind that these works were composed for a specific type of usage, where the demands on the quality of their content were small.

The End of an Honorable Tradition

The real significance of Reiche’s Tower Music is that it reflects the art and reputation of the wind ensemble, which dominated – in the 16th and 17th centuries – the (sacred) artistic music scene and was long able to defend ist position against the strings. The polyphony of motet and mass, but also the rich sound of past tradition, find a late echo here. The necessity of building up a new approach to this music is perhaps the reason why present performances often reveal a lack of understanding of its character and expression. This newly rediscovered and edited collection documents the importance of Reiche’s works both in musical and cultural history. It represents the last flowering of a wind music tradition which in the 18th century was already defunct.